ARTICLE: DANNY BARKER ROCKS ON

Originally published in OffBeat magazine, January 1994

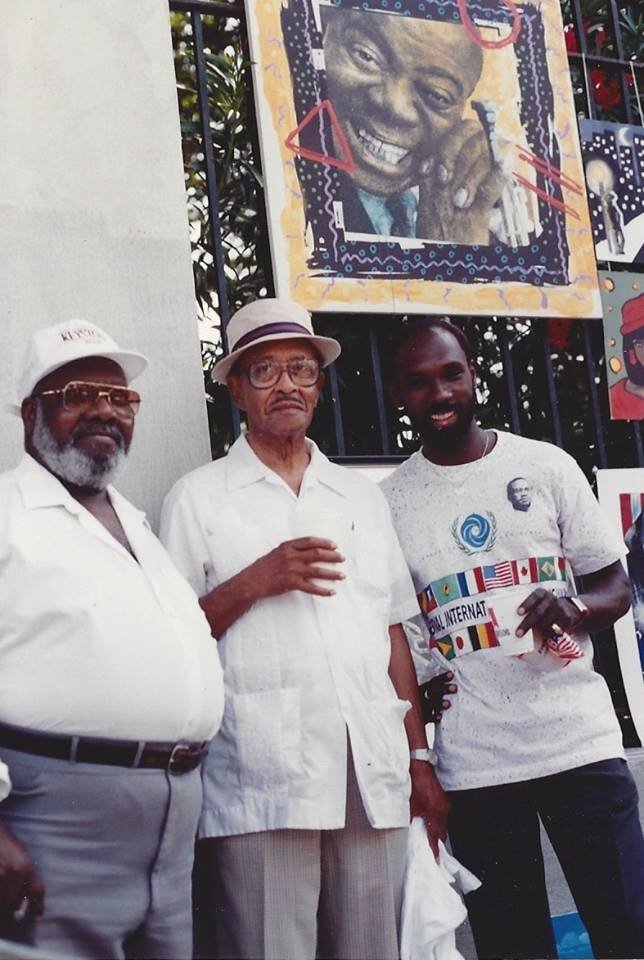

Danny Barker (center) shares a laugh with fellow musicians David “Chubby” Stevens and Greg Stafford. Photo by Michael Tisserand.

Danny Barker’s hand runs down the back of her neck and trails the sharp curves of her body.

“Just like an 18-year-old girl,” says Barker, turning his guitar over and polishing its back.

But he allows that the guitar is as well-seasoned as its player. Barker remembers receiving the instrument as a present from the Gibson company, back when he was playing in Cab Calloway’s band. And when he goes, he says, he’s willing it to local musician Steve Masakowski.

“Ain’t nobody that plays leads like that Masakowski,” he says. “Not me. I’m a rhythm man. That’s what always got me work.”

The hand strums down and precisely picks each string. Barker listens to the chord. Then suddenly he lifts the guitar and begins prodding inside the body, looking into the holes on the front.

“You never know when you might find some 40-year-old reefer,” he says with a straight face. “I never smoked it myself, but you had to have it, or the folks would think you’re square.”

Today’s lesson: You can learn a lot of things when New Orleans jazz musician, writer and historian Danny Barker picks up a guitar.

“I’ll be using my intelligent voice now,” decides Barker, leaning back on his living room couch.

Scattered throughout the room are microphone stands, amplifiers, guitars, boxes and photos. Barker piles papers and records on the front table, and the stacks are growing taller every day.

“I have ten different voices: my intelligent voice, my jazz voice, my night-life voice, my day-life voice, black Northern voice, black Southern voice,” Barker continues. “That’s interesting, eh? All the various voices you have to have when you have a brown or black paint job, you see?”

There are unopened CDs of his recordings — Barker has performed on more than a thousand sessions during seven decades. A stack of instruments kept to loan to neighborhood kids — one of Barker’s most far-reaching contributions to New Orleans has proven to be his work in the 1970s with the Fairview Baptist Church Christian Band. Fairview was a training ground for over a hundred young brass players, and helped spark New Orleans’ current brass band revival.

The walls are papered with commendations, ranging from certificates of appreciation from local elementary schools to his recent induction into the American Jazz Hall of Fame. Next to the telephone is a musicians’ union book and a list of phone numbers. Barker has a gig in two days and he’s looking for a reed man.

January has become a busy month for Barker. He recently returned to his regular Wednesday gig at the Palm Court Cafe. He’s king of this year’s Krewe du Vieux parade (“Not everyone can be the king of those bohemians,” he says). And he’s getting ready to record a new album. Pianist Butch Thompson will help with arranging, and the recording will feature some of Barker’s “spicy” songs, like “Palm Court Strut” and “Stick It Where You Stuck It Last Night.” Album preparation, Barker says, means “waiting until it’s almost time to do it, and then you get the feeling.”

Then, in the middle of his busy January, Barker turns 85 on the 13th. The city has proclaimed “Blue Lu and Danny Barker Day,” and a second line and party are in the works. Says Danny, “All of a sudden, people come from all directions that know me, that feel like they should celebrate me. But that’s New Orleans: ‘Let’s give a party.’”

The afternoon conversation in Barker’s house flows quickly from personal memories to jazz history. Behind his flickering smile and slyly arched eyebrows, the musician has been curating his own repository of knowledge from a life in jazz.

He turns the conversation toward a lesson he once learned in California. He appeared there in a movie — a comic short with actor Stepin Fetchit, around 1935, as well as in Andrew Stone’s Stormy Weather. “When you go to the movie studios they tell you, ‘Give me one of the biggest smiles, eyeballs and all.’ There’s the half-watermelon smile, the two-cent smile, the nickel smile,” he lists, and he wryly demonstrates each by turn.

Louis Armstrong had the biggest smile, he says. Young Kermit Ruffins is blessed with a “built-in smile.” But Barker admits that his own face is deadpan — he has to remind himself to think of something funny, he says.

Because, continues Barker, a musician learns that his smile can also be “a weapon — you use that to get in, and you use it to get out. It can be the most violent situation, you give them the smile that indicates that you’re backing out, and when you get out, you split. You got your instrument. The next day you go back to get your case.

“You see, America can be a very aggressive place,” he continues. “I’ve seen occasions where they have a brawl or a fight at the dance, and you play the music, and the people become more intense. You see, you got a rhythm in music, and when you throw a punch, you throw it in rhythm — we Americans are music-minded, and we go with tempo. I’ve seen a smart drummer slow down, and that slowed down the embattlement — until people stop and say, ‘Now what the hell were we fighting about?’ But you play the music of ‘Tiger Rag,’ the fists are flying in all directions.”

This is Danny Barker, raconteur-historian, drawing from his own unique perspective. The arc of Barker’s life spans the past century of American popular entertainment: Nat Shapiro and Nat Hentoff’s oral history, Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya, once singled out the then-New York-based musician “whose career parallels the evolution of jazz” — and that was in 1955. A New Orleans Times-Picayune concert review described the command of Barker’s “hard raspy voice summoned from an aging frame.” That was in 1972.

And during Mardi Gras last year, the newest jukebox hit was “Palm Court Strut,” penned by Barker just months earlier: “Do the Palm Court Strut, swing your butt/Do the Palm Court Strut, swing your butt/Shake it to the left, shake it to the right/Shake it to the one that you love all night.”

Barker has contributed to albums by Dr. John, Wynton Marsalis and Kermit Ruffins. His spoken song introductions on the Dirty Dozen Brass Band’s Columbia Records release Jelly prompted one reviewer to lecture the major label to “let him make his own record, where he can talk, sing or play as he chooses.”

Onstage, Barker peppers his memorable shows with stories from his career. “I’m a storyteller — that means I’m a liar,” he says. He is also the published author of two books on jazz history.

“They call me a Mark Twain,” he says, looking over a magazine article from the ’60s. “But I’m still an old, beat-up, dues-paying jazz musician. That’s it. A jazz musician.”

Danny Barker counts 55 musicians in his extended New Orleans family, but it was his aunt who once developed a corn on her finger, giving young Danny his first banjo ukulele.

“This kid showed me a few chords, and in a week’s time I could play ‘Ain’t Gonna Rain No More’ and ‘Li’l Liza Jane,’” recalls Barker. “So I’d go by the bar and start getting some money — this was before jukeboxes. I’m about 13, so I never was an amateur. I wanted that almighty quarter, that almighty dime.”

Barker then recruited friends into The Boozan Kings, a “spasm” band, the kind of outfit that kids were forming to earn extra money. “It was a little band you could hustle with,” he says. “Kazoo, washboard, sandpaper, a tin can with some rocks in it — anything to make noise with a smile. And you learned it from the minstrel shows that came through town, and you’d black up and wear a straw skirt.”

The Boozan Kings performed outside white taverns, collecting both tips and frequent racial taunts. The solution, as Barker later described in his autobiography, A Life in Jazz (Oxford University Press, 1986), was to incorporate the insults into the show: “One of the men laughed and mimicked Clarence … we kept that bit in the act.”

The young musicians soon graduated to private parties, including gigs in Storyville, New Orleans’ infamous red-light district. Barker remembers the prostitutes who paid him with money kept in their stockings. “The next time it would shock the other kid who was with you, but it wouldn’t shock you, because you’d seen it already,” he recalls.

In 1930, Barker married the woman who would become his singing partner, song collaborator and wife of now 63 years, Blue Lu Barker. The couple accepted Danny’s uncle Paul Barbarin’s invitation to move to New York. It was the Jazz Age, remembers Barker, and after Al Jolson’s movie, The Jazz Singer, “everything was ‘jazz this’ and ‘jazz that.’”

Work was to be found at places like the Nest Club and other East Side and Harlem late-night, post-curfew halls. There Barker learned the rules of New York: how to “double-up” on breakfast and lunch and, when it came to music jobs, “if you can do it, do it.”

During the course of 35 years in New York, Barker would mind these rules. He went on to perform with everyone from Jelly Roll Morton to Charlie Parker, and landed a coveted position playing rhythm guitar for Cab Calloway’s popular swing orchestra.

It was in Calloway’s band, remembers Barker, where he first met a young trumpeter named Dizzy Gillespie. Occasionally Barker would join Gillespie and others on a roof or in a side room during set breaks, when a few musicians were experimenting with a new form that would later be called bebop.

Where jazz went, journalists and scholars soon followed. “I’d go to parties and they’d jam me in the corner and ask me questions,” Barker says. “Some of the old black musicians — and white musicians — wouldn’t talk, but I told them, ‘You’re just hurting your profession.’”

Barker became an important source for journalists as well as a major contributor to Shapiro and Hentoff’s Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya. “I’m born under the sign of the goat,” he explains. “The goat, he’s very observant. He’s got great big eyes, and he looks straight at you … a musician sitting on a stand, he’s watching everybody. He’s in the front line.”

Some of these writers encouraged Barker to chronicle his own stories, and the musician kept a running diary of his years in New York, writing his observations on newspapers and scraps of paper. Returning home from a gig “tired but fresh,” he would fill bedside tablets with memories of the day. “You’re laying there, relaxing, and you’re laughing at a situation that happened to you, and you want to put that down,” he recalls. “And I was boozing then, and when you’re boozed up, things just flow in your mind that you wouldn’t say if you were sober. Then you doctor them up afterwards if you were too naturalistic.”

In addition to the hard-to-find A Life in Jazz, Barker published Bourbon Street Black (Oxford University Press, 1973), an out-of-print study of New Orleans musicians. But most of Barker’s written work — including several completed stories — is collected in cardboard boxes and plastic bags around his house. “See that box there?” Barker asks, getting up to point under the table in the dining room. “And see that box in the corner over there? And you stand up and see those doors that people don’t see? I got a back room there, with reams and reams of stuff. Boxes of stories.”

It’s Saturday afternoon at Trombone Shorty’s, and a few patrons have escaped the bright afternoon light to listen to a friend strum a guitar.

“Mr. Barker! Danny!”

“Hey Cuz,” replies Barker, recognizing one of his many relatives in the city.

Young jazz singer John Boutte pulls a chair alongside Barker. “Hey Mr. Barker, do you know ‘Someday You’ll be Sorry” in A flat? You know ‘You Can Depend on Me’ in B flat?”

“Yeah,” Barker obliges, and the two sing together softly.

A woman in a pink dress starts dancing next to Barker. “Hey Danny, play ‘Palm Court Strut!’ Shake it to the right, shake it to the left.” He does. So does she.

Someone yells, “Hey Mr. Barker, where was the worst place you ever played?”

“I played music in Hell’s Kitchen — that’s in New York. Once I played a club with a blood stain on the floor from where a person was killed. The owner wouldn’t let you wipe up the blood. See, it’s hard to wipe up Colored blood — you have to paint over it.”

The sound of laughter in Trombone Shorty’s. “That’s what you call Treme humor,” adds Barker in an aside. This is his jazz voice now. His night voice, on a sunny afternoon.

“I like to write about the risque-living people,” he says. “It gives me a lift to know I’ve had to stoop down to that level of existence. You absorb this country and all the elements of people — the side-by-side lifestyles of day people and night people.

“People at night, they don’t plant nothing — they’re not farmers, they don’t build no buildings. All they do is live off the earnings of the day people. These wise people all over the world, they don’t know about the night people, the denizens of the dark. I’m very observant — that’s why I’m 84.”

Many of Barker’s most popular compositions, including “Palm Court Strut” and “Stick It Where You Stuck It Last Night,” are as full of double entendres as the word “jazz” itself.

“A lot of people buy these records, but they don’t leave it out in the open,” says Barker. “They wait until the party gets raunchy, with everybody letting their hair down, and swing it to the right and swing it to the left, and doing the ‘Git Down’ and all them different dances — they call it the movements of the lower part of the human frame.

“But when it’s polite society around, it’s very blasé and very cool — they’d never play a record like that. But after the party’s gone, they dig out ‘Don’t You Feel My Leg.’

Barker is still in demand as an expert witness, having recently contributed his observations to numerous books and documentaries on subjects ranging from baseball to Storyville. He hopes to publish another half-dozen books of his own. “I’ve got the material ready to go,” he says.

But most of Barker’s days are spent at Blue Lu’s side — the singer has had health problems, and Barker assists with physical therapy. He looks forward to performing with his wife again, but for now he says, “We sit down at home and have a little ball amongst ourselves … that’s what marriage is all about.”

Recognition of Barker’s legacy and talents continues to grow, at which the musician either professes or feigns surprise — it is sometimes hard to tell. “That was a strange thing, when the Hall of Fame called me,” he says. “I asked them, you’ve got all the giants of jazz up there. Why are you putting me up there? Seriously. Because I don’t play a lot of solos. I don’t want to discredit the high authority of the Jazz Hall of Fame people.

“And they said, ‘Well, you’ve done some things that nobody else has done. Very few people can say they’ve played with King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. And they hired you more than once.’

“So I sit there and I play rhythm,” Barker concludes, “the proper chord the best I knowhow, and with a natural New Orleans feel, like a heartbeat.”

Danny Barker pounds his chest.

“You hear that? Solid.”

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Shortly after this interview, Danny Barker was diagnosed with cancer. That Mardi Gras, he reigned as king of Krewe du Vieux. He died soon after — on March 13, 1994. He was 85.

For many years following the death of Barker and his wife, Blue Lu Barker, the artifacts and papers from their lives in jazz remained in the shuttered Barker home. Then, a decade after I first visited Barker, I found myself forcing my way into his home with a hammer and crowbar. With the permission of his daughter, and accompanied by my friend Jason Berry, I was returning to see what could be salvaged from the floodwaters of Hurricane Katrina. Much was destroyed. Yet Barker had stored some of his works on upper shelves in his back room. These boxes were dry, albeit coated in mold. This collection, now restored, is now part of the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University.

Writing this article also provided an invaluable lesson to me about the importance of a good editor. Michael Sartisky, working with me on an early version that appeared in Louisiana Cultural Vistas magazine, encouraged me to come up with a better lead than what I had originally provided. I went back to the interview tapes and discovered that Barker, while clipping the tiny tape-recorder microphone to his shirt collar, had commented about his “various voices.” Barker, it seems, was muttering to himself about what voice to use in our interview. His comments, which I had completely missed the first time I listened to the tape, would be quoted by the preacher who delivered Danny Barker’s eulogy, as well as by Nat Hentoff in a column for the Village Voice. I can’t think of a single quote in any story I’ve written than I treasure more than this one, so I’ll finish here with Barker’s own words:

“I have ten different voices: my intelligent voice, my jazz voice, my night-life voice, my day-life voice, black Northern voice, black Southern voice. That’s interesting, eh? All the various voices you have to have when you have a brown or black paint job, you see?”